This exhibition assembles photographic material that Gerhard Richter has been gathering since 1960. A small part of this collection consists of clippings from newspapers and magazines, which seem mostly to address a youthful interest in “shocking” images on themes of sex and death. Far more compelling are the many snapshots which chart Richter’s investigation of the relation between photography and painting as instruments of representation and, in so doing, pose intriguing questions: Is it true, as Jonathan Crary argues in Techniques of the Observer, that photography became “the dominant mode of visual consumption” because it “preserved the referential illusion more fully than anything before it”? Can painting challenge this dominance by mimicking what Clement Greenberg calls photography’s “transparency,” meaning both the radical spatial depth and the seeming immediacy of its process? And how fully does photography “preserve the referential illusion,” given that we mistake photographs for their referents infrequently and, even then, rarely for long? Much of Richter’s work of the last thirty years – though by no means all of it – has investigated the liminal region where photography and painting overlap, interrogating their capabilities as instruments of representation. In the current exhibition, the snapshots that map this interrogation break down roughly into three gropus: those used in exhibition mock-ups; those which have been painted upon; and those that work through painting’s genres.

Richter’s exhibition mock-ups consist of photographs of clouds collaged onto sketches in which rooms are rendered in dramatic perspective. The scale of these collages’ components demonstrate that, were any of these ventures to be realized, the expanses of cloud would occupy most of the wall from floor to ceiling, in rooms ranging in size from generously proportioned domestic spaces to monumental public halls which reduce their occupants to insignificance. While the scale of these maquettes is fairly clear, what the photographs are supposed to represent is not. For example, one collage shows a space the size of a large living room, with a series of photographs along each wall. Since Richter paints from photographs, he might have produced this piece to test the effectiveness of a series of large paintings of clouds. The maquette’s usefulness in such a trial, however, appears limited. Since the collaged images are snapshots, their transparency – to invoke Greenberg again – makes them seem better suited to represent windows of massive photographic prints. But this reading of the snapshots as windows or photographs remains provisional, since Richter’s own works – the famous Administrative Building (1964), for example – demonstrate that an oil painting smudged with a little turpentine can very effectively mimic the lack of focus which lends authenticity to snapshots by giving them a sense of spontaneity. Our ability to determine the role of the photographs in these maquettes is hesitated by an awareness of Richter’s wryly ironic use of the painterly touch – precisely what we expect to separate painting from photography – to blur the boundaries between these two media.

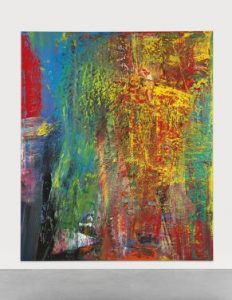

While Richter’s exhibition mock-ups and painterly canvases obscure the distinction between painting and photography, the photographs upon which he has painted emphasize the differences between these modes of representation. Using snapshots of mountain ranges for a surface, Richter covers over parts of the image with a thick layer of paint, more or less obscuring what is beneath it. The paints have been mixed little, if at all, and therefore seem artificial. They have been laid down as streaks or smears, so no identifiable forms or depth cues are delineated. In some cases, the paint has been tamped lightly, giving a stippled effect to its surface. As a result of these treatments, the paint tends to appear as a flat patch of colour floating on the surface of the photograph. The exceptions to this tendency are photographs which have had substantial areas painted out. In these images, the masses of pigment tend to follow lines suggested in each photograph so that, for instance, the sides of a valley will be obscured, leaving only the peaks in the background open to view. The brilliance of the exposed mountain tops makes them come forward visually, so that they give the sense of being in front of the layer of paint. In both cases, the painted surface is too opaque and lacking in depth to be confused with the photographic image.

Given that photography first became widely available during the mid-nineteenth century, Richter’s interest in it as a counter-term to painting suggests a concern with the examination of painting’s changing status in the bourgeois era. This suggestion is given additional weight by Richter’s photographic investigation of painting’s genres, which takes up still-life, land-scape, the nude, and portraiture. Richter’s categories are those of the bourgeoisie, as are his subjects and compositional arrangements. The still-lives, with their sparse orderings of candles, wine-bottles, fruits and skulls, have more in common with the studies of everyday objects by Manet and Cezanne than with Willem Claez Heda’s virtuoso displays of seventeenth-century Dutch luxury. More significantly, several railway views are included among Richter’s landscapes, and there is no denying the historical specificity of that motif to painting in the moment of the bourgeoisie’s ascendancy: think only of the numerous Impressionist images that depict either railroads themselves (Monet, for example), or locations that this mode of travel made newly accessible as leisure sites for the middle-classes (Monet, Manet, Renoir, etc.). Richter’s images of electric commuter trains operating in post-World War II Germany are not attempts to recreate the France of the late nineteenth century. But, significantly, the trains in both eras exist to link the suburban retreats of the middle-class to the urban commercial cores which define its existence.

Richter’s strategy of exploring painting as a bourgeois art form by using the technology that emerged to compete for the same audience is not an attempt to save painting by demonstrating that it can do anything photography can (a pointless task anyway since, as Greenberg notes, the issue really is that photography does it faster), or that painting can go places where photography cannot follow. Rather, this tactic acknowledges the importance of realizing that, by painting, one invokes a system of signs operating in the midst of history, and that, consequently, the significance of a painting is partly determined by the range of other sign systems available during the moment in which one paints. As the range of available sign systems changes, so does the meaning of choosing any of the systems in that range. To decide to paint in 1965 meant, in part, to decide not to photograph. That same meaning obtains today, but would not have obtained in 1765. Similarly, today, a decision to paint implies a choice not to use digital imaging technology, though it did not have that implication thirty years ago. The meaning of a brush stroke has shifted somewhat in the several decades that Richter has been painting. And, while his practice points to this shift, it also shows that, in important ways, painting’s informing context remains the growing industrialization of life and the senses that continues to define the bourgeois epoch.